Last Thursday I was fortunate enough to meet Sir Alan Parker for lunch at the Chelsea Arts Club. My former creative partner, Paul Smith, who is Ogilvy’s Europe, Africa and Middle East creative director, hosted the lunch. We met in the bar, where we bumped into a close friend of Alan’s, Gray Joliffe, the cartoonist, who currently has an exhibition of his work at the Club. The idea of the lunch was to catch up on old times and find out what Alan was up to and, of course, have a good time. He’d made a number of commercials for Paul and me in the seventies, all were successful; most won awards. Since then, he’s directed 14 feature films, including Midnight Express, Angel Heart, Mississippi’s Burning, The Commitments and his most recent movie, The Life of David Gale. Neither Paul nor I had seen much of him since working with him in the seventies, although I had bumped into him at a restaurant just before Christmas.

It was an enjoyable lunch, made all the more so by Paul’s choice of wine: a rather splendid Savigny-lès-Beaune. Alan regaled us with many stories from his movie career in Hollywood, none of which I will repeat here for fear of incurring libel suits. He went on to speak of his early days of directing commercials.

It’s been often documented before, but it’s worth repeating how Alan got started. The ad agency where he worked in the late sixties, Collett, Dickenson, Pearce occupied a crummy building in Howland Street, just round the corner from Tottenham Court Road. It had a huge, empty, unused basement that only seemed to be pressed into service for the agency Christmas party.

Alan was a copywriter at the agency and, when he wrote a script, got into the habit of shooting a test film in the empty basement. Often, these test films used members of staff as actors. The accounts department was one of Alan’s favourite happy hunting grounds for characters to appear in his commercials. His partner in crime in these burgeoning directorial efforts was Alan Marshall, who had been a film editor, but who now acted as Alan’s producer and editor. But, in one way, Alan Marshall was also something of a mentor.

Alan Parker told us the story over lunch about one of his earliest efforts, a ‘three-hander’ for Hovis bread. It featured a trio of charladies discussing the merits of Hovis. Alan had never shot a commercial with three actors before and he was terrified of mucking it up. He did some rehearsals but still wasn’t confident about what to do on the actual shoot day. After everybody had gone home, he went back to the basement with Alan Marshall and went through the shots he intended to cover. Marshall, as an editor, knew exactly which shots Parker should and should not do. He told Parker to dump some of the intended shots, but added others that Parker hadn’t considered. The result was a successful film that edited together like a dream, helping to boost Alan Parker’s confidence as a director.

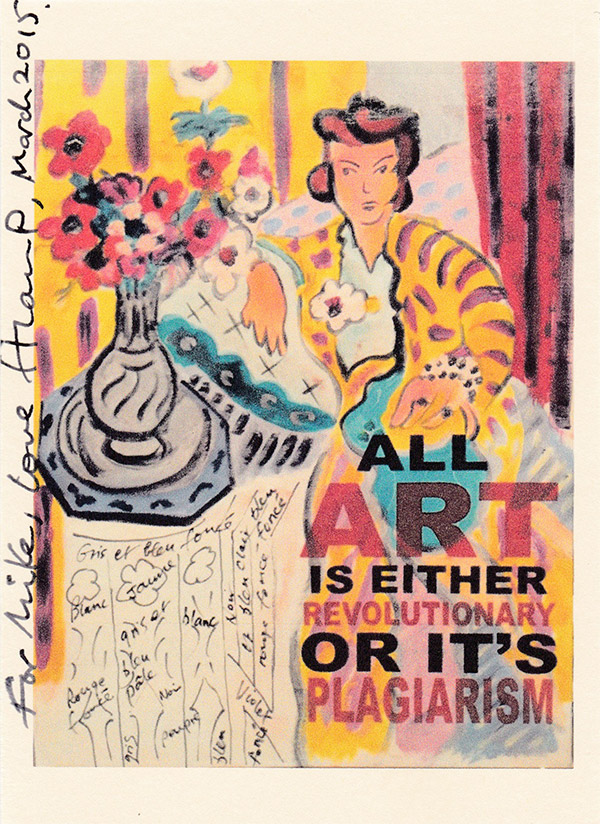

All too soon, two hours had flown by, and Paul had to rush back to his office. This left Alan and me to decide what to do with the half bottle of fine, red Burgundy that remained. We made the only sensible choice and proceeded to drink it. It was only at this stage, after Paul had left, that Alan revealed that he had taken up painting. He showed me some printed cards of his work and gave me one to take away. I asked him to sign it, which he did. He told me that he has access to the art college over the road from his office in Chelsea. He goes in there when the place is empty at the weekend and works on his canvasses, which currently he is doing in the style of Matisse. Working in a large, empty, open space? I can see why he might feel at home. Doesn’t that ring a bell? It must be just like the old days, in the large, empty basement at Collett, Dickenson and Pearce.

If you want to read more about Alan, visit his website. It not only tells you about all his feature films but also features a show reel of his favourite ads from way back when. I don’t think, though, that as yet it shows his paintings. That’s something we can all look forward to in the future.